Por Edward Fox |

CRÍTICA URBANA N.9![]()

|

The urban-rural dichotomy is as old as human civilisation. Although it may have adopted varying manifestations over the centuries, it has changed very little in its essence. As cities have multiplied and grown, both in size and complexity, this dualism has been reinforced

Today, well over 50% of the world’s population is now urban but this vast mass of humanity is concentrated in barely 3% of the land mass. Most of the remaining 97% is exploited to meet the needs of distant city dwellers with no stake in – or understanding of – the impacts.

.

The Urban-Rural Dichotomy

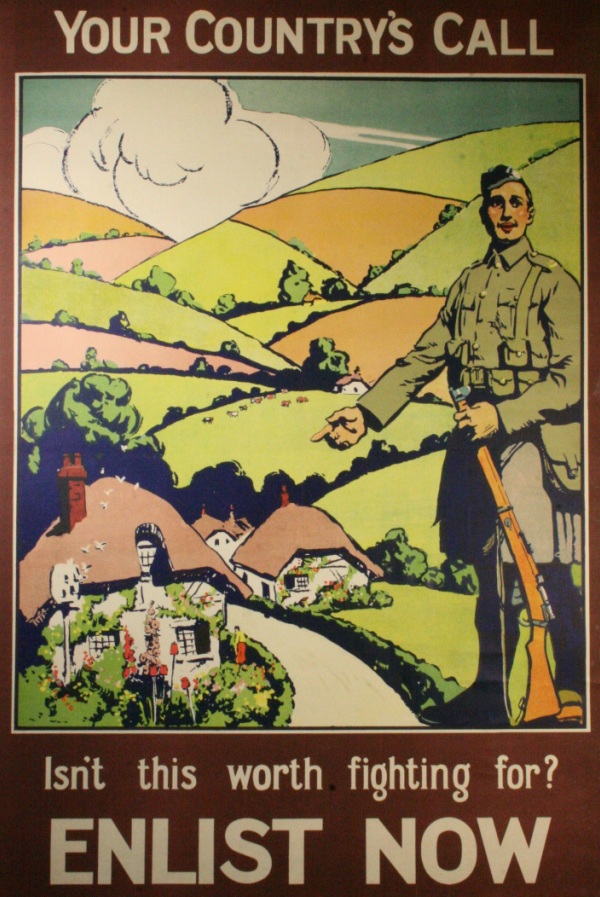

The growing concentration of learning and power in urban centres has led to an idea of ‘the rural’ constructed from an urban perspective, mythologising the countryside in opposition to the urban, as a timeless place of beauty, tranquillity and health, or as the embodiment of an elusive national identity.

Like the mass-produced jams and chutneys which seem to bottle the authenticity of the rural, this ideologically driven construct preserves an imaginary ideal of the rural landscape which is increasingly at odds with contemporary pressures and demands. Accelerating urbanisation has at one and the same time intensified the demands on the countryside to provide a range of critical services to urban populations (food, water, waste, energy, infrastructure …), while strengthening the mythology of the rural idyll. Below the superficial veneer of an unchanging, idealised pastoral landscape lies a fragile and contradictory reality of ecological desertification, high-tech/low-employment agriculture, battles over old and new forms of energy generation, subsidy-dependent hill farming, aging populations and dwindling village communities.

First World War Poster Encouraging Young Men to Defend an idyllic British

Countryside

Landscape and the Rural Idyll

Landscape is a slippery word. We think we know exactly what it is but as soon as we take a closer look it seems to evaporate or to segue into other equally evasive ideas and concepts: nature, countryside, scenery. Landscape Architecture, as a relatively new profession, is concerned with the construction of landscape. This explains the difficulty we as a profession have in communicating our role to the world, because landscape is popularly thought – or felt – to be somehow natural and given. Whereas a building is unambiguously a human creation, with landscape the boundaries between the designed and the natural are blurred.

The word originated as a term for western painting which broke away from the human figure – and usually biblical motifs – as its principal subject matter, and adopted the countryside as its primary focus in the 16th and 17th centuries. The selectively framed view led to an iconography of the rural in which the working countryside became loaded with layers of symbolic meaning, often drawn from mythology or philosophy: arcadia, innocence, the sublime. The Claude Glass, supposedly invented by Claude Lorraine, was a concave, darkened mirror which concentrated and intensified the landscape and was an obligatory accoutrement for 18th century travellers, mediating between the human gaze and the raw landscape. The Claude Glass eventually gave way to the camera, the instamatic and now the mobile phone, chemically or digitally reinventing the framed view, mediating and distancing us from the complex, contradictory, lived reality of these scenes as communities, as ecosystems, as industrial production lines.

Such is the power of the romantic myth of landscape, that it is still conflated in the popular imagination with the rural idyll, an idea which in turn blurs with a confused sense of nature. Landscape as a kind of frozen nature or framed view, generates a powerful sense of an unchanging or unchangeable world outside the urban, and possibly beyond the human, which has conditioned the way we view and engage with the rural world. This tangled mesh of ideas, disguises the fact that the rural landscape is as much an ideological ‘construction’ as any town or city and that the reality is far more complex, dynamic and interesting than the myth.

Artwork by Gary Turner Highlighting the Ubiquity of the Picturesque in the British Countryside. Photo: E.F

British Rurality

The UK is one of the countries where the urban-rural dichotomy is most radically expressed. In one of the densest and most highly urbanised countries in the world, as little as 17% of the population is defined as rural (Office of National Statistics, 2019) and only around 5% is actively engaged in agriculture, but over 80% of the land mass is still non-urban (CORINE, European. Environment Agency). In a highly populated and developed country, the demands on the agricultural sector are immense and even though around 40-45% of our foodstuffs are imported, the British countryside is still one of the most intensively farmed in the world. It is also a landscape which has been exploited and reconfigured over centuries: mined for its mineral wealth, quarried for its stone, deforested for its timber and infilled with urban waste; one whose watercourses have been canalised, dammed and redirected for transport, energy and sewage; and one which is carved up by a complex mesh of roads, railways, power lines and a multiplicity of infrastructural networks overlaid and interwoven across Britain’s ‘Green and Pleasant Lands’. No part of our cherished countryside can be considered in any way as natural or unspoilt.

The role of the rural landscape as a ‘Machine for production’ sits alongside – and often in opposition to – its recreational and cultural significance as a ‘Commodity for consumption’. Walking is an activity which has been deeply embedded in British middle-class culture for 200 years and continues to be an extremely popular activity. Today we can add to this; cycling, fishing, climbing, swimming, canoeing, horse riding, yoga retreats, garden visits, bird watching, and many more. The common denominator is the need to be in the countryside and out of the city: to ‘escape’, to ‘recharge’, to ‘get some space’ or ‘breath clean air’, all typical of the language associated with the rural, a realm which continues to be defined in opposition to the urban as a place of health, purity and tranquillity. Tourism iconography as well as marketing of everyday products continually reinforces these stereotypes.

Underpinning all of these activities is the need to maintain a rural aesthetic which meets the expectations of urban visitors, as well as rural second home owners and commuters. The countryside is therefore planned, administered and managed as much as ‘scenery’ or ‘landscape’ as it is for its productive efficiency. The intense controversies over new infrastructures which threaten to damage or ‘deface’ our countryside– from wind farms to roads or high-speed railways – reflect the depth of feeling and cultural importance of the conservation of the eternal English landscape. Arguably, the radical opposition to Genetically Modified crops may also be attributed at least in part to a sense that these undermine the ‘authenticity’ of the rural world and its products, one of the many deep-rooted values associated with our rural landscapes.

So, the British countryside is at once a utilitarian production line for raw materials and a cultural object of consumption. To these values would now have to be added its function in providing critical environmental services, such as flood mitigation, decontamination, cooling, ecological diversity, etc. Can the rural landscape meet these three different demands?

Tourism marketing frequently associates an idealised countryside with national identity

The Construction of the British Landscape

The ‘construction’ of the British landscape predates the industrial revolution and has its origins in a struggle which took place progressively over several centuries; the ‘Enclosures’. Britain led the world in the creation of a capitalist economy and, effectively, in ‘monetarising’ its land assets. The Enclosure of land and the establishment of defined property rights is seen by many as the origin of this process. ‘The Enclosures’ took place from the 15th to the 19th century, during which time the medieval system of land ownership and management was gradually eradicated. Under this system, although land was actually owned by the crown and controlled by a tiny number of aristocrats, it was cultivated by village communities collectively on a rotational basis, mainly to meet their own needs. These communities enjoyed rights over a ‘commons’ where they would pasture their animals. The Enclosures involved the parcelling up of land for private ownership and use, first by wealthy landowners and increasingly by a growing gentry class, and the progressive removal of collective agriculture and the commons. Large tracts of land were fenced, walled or hedged around to create pasture, mainly for sheep, whose wool was an increasingly valuable commodity. The process was often small scale and opportunistic in its early stages but, cumulatively, came to represent an existential threat to the way of life and stability of many rural communities. It led to the widespread abandonment or decline of villages all over the country and in places was violently opposed, at times giving rise to huge uprisings. The Enclosures led to the growth of a gentry class of landowners, the spread of commerce and the textile industry, and the flight to the towns and cities of ‘masterless men’. It is considered by many as the origin of the industrial revolution itself.

The 19th century accelerated the decline and depopulation of the countryside, with the further flight of men to urban centres to work in factories, and also the beginnings of new science and technologies in agriculture which made larger scale, more intensive farming more viable. The twentieth century has only concentrated ownership and intensified land use further and the drive to generate food surpluses in Europe since the second world war has led to even greater monocultural farming, removal of hedgerows, woods and meadows, and the extensive use of artificial pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers. In effect, the ‘eternal’ British countryside is the product of centuries of brutal appropriation and enclosure of common land and an ever-increasing drive towards large scale, intensive agriculture. Ironically, one of the most powerful symbols of the rural idyll, the sheep, was in fact one of the most important instruments in the remaking and continuity of the British pastoral scene.

.

Landscape and Englishness

Despite the ruthless capitalisation of its landscape, the UK is, paradoxically, also one of the countries where the ideological construction of the rural landscape has been most powerfully embedded. The birth of the English Landscape tradition in the 18th century, was strongly rooted in the idea of a return to a golden age when man lived in harmony with nature. ‘Improvers’, as they were known, such as William Kent and Capability Brown, broke radically with the ordered and controlled geometries of the dominant renaissance and baroque landscapes of France and Italy. The iconic landscapes of Stowe, Studley Royal, Chatsworth and others aimed to recreate the Arcadian landscapes of Claude Lorraine and others in the estates of the increasingly wealthy British aristocracy. These early landscape revolutionaries cleared villages, dammed streams, and removed hedges and walls to generate the illusion of an unbounded, uncorrupted, idealised English landscape, free of any evident human influence. As Horace Walpole said of William Kent: “…he leapt the fence and saw that all nature was a garden…”

In parallel, during the 18th century, the growing middle class sought British equivalents for the familiar landscape iconography of Italy, the Alps or France, to reinforce a growing sense of national identity. They turned their attention to the sublime qualities of the mountains, heaths and moors of Britain’s uplands. What had previously been considered as bleak, dangerous wilds and wastes, now attracted the attention of the educated classes, seeking to experience the sublime. This change is reflected in the dramatic contrast between Daniel Defoe’s 1725 description of the High Peak In Derbyshire (now part of the Peak District National Park) as, “the most desolate, wild and abandoned country in all England”, and William Wordsworth’s definition of The Lake District, less than 100 years later in 1810, as a “…sort of national property in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy.” Wordsworth’s claim, radical at the time, reflected a cultural appropriation of the ‘unspoilt landscape’ as a shared national heritage. This view persisted into the 20th century and gave birth eventually to the creation of the National Parks soon after the second world war.

The National Parks and the associated system of designations were the culmination of a progressive ‘museumification’ of the countryside and of the adoption of the idealised British rural landscape as a primary symbol of national pride and identity. The growth and spread of visual and digital media over the subsequent 75 years has only served to reinforce this deep-seated cultural bias.

Chatsworth House and Gardens, Derbyshire, artificially created by demolishing a village, damming a stream, removing all

field boundaries to create a romanticised view of a rural idyll. Photo: E.F.

A Rural Pathology

The iconic qualities of the British countryside today are as strong as ever and as important to the national psyche as they are to the national ‘brand’. Numerous layers of government, from the planning system to the farming subsidies, help to protect and preserve this vital national asset. Yet, the rural idyll disguises what may be seen as a pathological condition. The countryside faces multiple crises at almost every level; environmentally, ecologically, socially and economically. Climate change and Brexit both pose significant threats to its continuity, although of very different magnitudes. The tensions between the countryside’s tripartite functions; as machine, as commodity and as provider of ecosystem services, may be reaching breaking point.

On the one hand, the need for increased agricultural production appears to require more land and more intensive farming methods, which threatens to further contaminate our soils, air and waterways. Sheep farming, the mainstay of almost all of the UK’s upland landscapes, relies almost entirely on subsidies, largely EU generated, for its survival and artificially maintains these landscapes as bare, deserted, ‘green deserts’. The UK is among the least ecologically diverse countries in the world (State of Nature Report 2016) and also has one of the smallest extensions of forest in the developed world, at approximately 13% of the land area, compared to France at 29% and Germany at 34%. Growing bodies of evidence point to the problems this raises in terms of flooding, air pollution and warming, all likely to become more acute in coming decades as climate change accelerates.

At the same time, socially, the countryside is in crisis. Of the small percentage of the population which is defined as rural, barely a third is actively engaged in agriculture. In other words, the majority live in the countryside but work in the city or make a living in ways which are not actively related to the landscape around them. This generates unstable and precarious communities where living blurs with tourism and leisure. The Air B&B phenomenon, second home ownership or increasingly flexible live-work arrangements generate communities where the distinction between the urban and rural is ever harder to draw. Rising property prices and declining job opportunities drive the young and talented away from rural communities leaving an aging population suffering from poor communications, poor access to services and amenities and increasing isolation.

.

Possible Futures

In effect it could be argued that the tension between the conflicting roles of the rural: the picturesque and the performative, has reached breaking point. Our outdated romanticised expectations about how the countryside should look underpin a conservation policy which is ideologically driven and directly at odds with the performative demands on this realm, whether environmental, ecological, social or economic. At every level, the countryside we have constructed is under threat, and there is an urgent need to question our assumptions about what the rural landscape looks like, how it operates and what it is for. Part of the challenge is to extrapolate from current trends to begin to reimagine possible future rural landscapes. The exploration of hypothetical scenarios for rural futures may begin to reveal a wealth of new potentials:

The Drowned World – Increasing extreme weather and rising sea levels seems likely to flood many of our valleys and agricultural lands. Can we reframe flooding as an opportunity? Can we imagine landscapes of aquatic living under bird-rich skies, wetland agricultures and intensive fish farming?

Disenclosure – The model of privatised and centralised ownership of farmland has been an ecological and social disaster. Could we imagine new forms of collective ownership or rights over tracts of rural land? What would happen if we radically restructured our countryside, reconfiguring fences, walls and hedges? What would the landscapes and lifestyles created by this ‘return to the commons’ be like?

New Nomads – The rural economy is seasonal and fluctuates to rhythms of cultivation and tourism. Second home ownership has pushed house prices beyond the reach of many rural dwellers. Could we conceive of new forms of living based on the campsite and caravan rather than the unaffordable home? Flexible, nomadic communities moving from place to place in response to seasonal economies?

The Rural Powerhouse – The rural landscape has been marked by processes of energy generation for centuries, from wind and watermills to coal mines and spoil heaps. Renewable forms of energy generation will also be transformers of our landscapes. How might we imagine an intensively energy-generating countryside? How would this impact on the lives and landscapes of local communities?

The Wild Woods – The landscapes of Britain’s uplands have been characterised as an ecological desert. Rewilding and reforestation have been proposed as radical solutions to this ecological crisis, but what would this mean for local communities and economies? The woods and forests have long been mythologised as places of danger and evil. Can we conceive of a return to living in and alongside the woods as a positive? Can we invert the Red Riding Hood myth and learn to love the wolf?

If Landscape Architecture is about more than designing the spaces between urban developments, it would seem to be an imperative for us as a profession to begin to reframe and rethink our ideologically constructed imagery of the rural landscape. If we are capable of conceiving alternatives, perhaps we may also be capable of reconstructing our rural mythologies to generate potent new symbols of a richer, more diverse and ultimately more functional and healthy future.

.

Nota sobre el autor

Ed Fox es director del Máster de Arquitectura del Paisaje de la Universidad Metropolitana de Manchester (MMU), puesto que ocupa desde hace 8 años. Anteriormente ha pasado más de una década trabajando en estudios de arquitectura del paisaje en Mánchester. Sus intereses como investigador se enfocan en temas del paisaje rural y periférico y ha publicado también artículos sobre la rehabilitación de ríos urbanos.

| Para citar este artículo: Edward Fox. Reconstructing the rural. The Role of Landscape Architecture in Reimagining the UK’s Rural Landscape. Crítica Urbana. Revista de Estudios Urbanos y Territoriales Vol.2 núm. 9 El paisaje. A Coruña: Crítica Urbana, noviembre 2019. |