Por Dawn Parke, Eddy Fox and Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon |

CRÍTICA URBANA N. 37 |

The health of an ecosystem is measured by its diversity, connectedness and adaptability. If cities can be seen as complex ecosystems, in social and economic terms as well as in the ecological sense, then contemporary cities are profoundly unhealthy and dysfunctional. To this extent, the restoration and reinforcement of these measures must be the prerogative for anyone engaged in the design or planning of urban environments.

If we are to educate future generations of professionals to understand and address these challenges, and not simply to repeat the commercially driven, normative models which have contributed to the current crises, we must begin with the direct, embodied experience of urban space. Students must learn to connect the abstractions of two-dimensional mapping, or the semi-divine visions afforded by satellite photography, with the lived experience of the city, as seen, heard and smelt through our human senses, at the human scale. In an age of ever more accessible and rapid software tools for the analysis, design and visualisation of space, our own experience is increasingly mediated and distanced from the places we are designing. Scale, climate and context become negotiable, flexible concepts, distanced or entirely divorced from the physical reality which our lines and points in digital space ultimately engender. The challenge of our current age is not to train students to become more proficient users of an ever-wider spectrum of software, but to reconnect them with their own embodied sense of space, and to understand landscapes as manifestations of cultural and ecological process, embedded in a specific time and place.

Figure 1. First impressions of the site. Student name: Wing Chi Shek.

This article is a reflection on a pedagogical experiment with just such a learning process. A multi-cultural group of students on a Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) programme, from diverse professional and educational backgrounds, begin their learning journey by encountering an urban space in all its dimensions: human, ecological, material, sensory and cultural, before negotiating a shared proposal for an intervention, which reflects relationships between the human and the natural. The project acts as a framework for multiple simultaneous encounters: with the city; with embedded cultural and environmental associations and assumptions; with creative design practices; and with the space itself, not as an abstraction but as a dynamic and complex ecosystem.

Context

The MLA programme at the Manchester School of Architecture is a two-year course which enables students from related educational and professional backgrounds to ‘convert’ to landscape architecture, graduating with a professionally accredited qualification. The cohort is comprised of individuals with diverse nationalities and professional backgrounds, including some with no prior design experience. They are embarking on a learning journey transitioning to an unfamiliar subject area, and a new educational, cultural, and physical context. The immediate challenge is to incentivise a collaborative group culture, acknowledging and respecting the variety of skillsets as well as cultural associations and experiences. The course aims to foster a shared process of discovery of the idea of landscape by challenging normative assumptions and the conventions of practice, which often tend to distance students from their own embodied experience.

The process begins by cultivating a shared language, through artistic visual representation of direct sensory engagement with place underpinned by critical reflection. The emphasis is on building conscious awareness of emotional and physical sensations, and the natural processes influencing those encounters, rather than focusing on the fixed architectural elements and objects in space. Grounded in students’ prior experiences, the approach encourages peer learning and challenges ingrained assumptions, repositioning the landscape architect’s role as one of reflection and responsiveness, rooted in sense of place. Manchester serves as the primary laboratory for this transformation. It is through students’ varied responses to the city that a collective dialogue emerges, offering a foundation for investigating the complex, embodied nature of landscape.

Project Overview

Positioned at the beginning of the student journey, the project runs over a four-week period. A carefully scaffolded learning approach, supports students in developing an understanding of landscape as both concept and lived experience, while cultivating creative and artistic skills that foster personal expression and a shared visual language. The process comprises a series of interconnected activities unfolding both on site and in the studio.

Students began with a site visit to capture their physical and emotional impressions through sketches and mappings, combining representational and abstract techniques, recording ephemeral qualities and patterns of use. This approach acknowledges that “arts-based approaches and associated investigation techniques, which take a qualitative approach, provide appropriate tools for revealing the deep meaning behind the landscape.”.

In the studio, groups developed collaged visuals and/or sound pieces to articulate a collective landscape narrative. Figure 2 shows students drawing to music, a practice that stimulates creativity while encouraging reflection on time, rhythm, movement, form, and texture in landscape. Crucially, this activity helps reduce apprehension around drawing, challenging the notion that artistic skill is a prerequisite for visual thinking. By levelling the perceived hierarchy of ability, it fosters a sense of equity and inclusivity, resulting in a more open, supportive and collaborative artistic practices evidenced in figure 3.

Figure 2. Students drawing to Music. Image Credit: Dawn Parke. Figure 3. Collaborative collage-making. Image Credit: Sandeep Menon.

Theoretical perspectives and artistic precedents are examined through abstract and diagrammatic representation, alongside critical discussion and comparative analysis. Students are encouraged to engage reflectively with these ideas, identifying which align with their own experiences and which do not. This process fosters a more nuanced, personal understanding of landscape, while grounding their emerging approaches in critical theory.

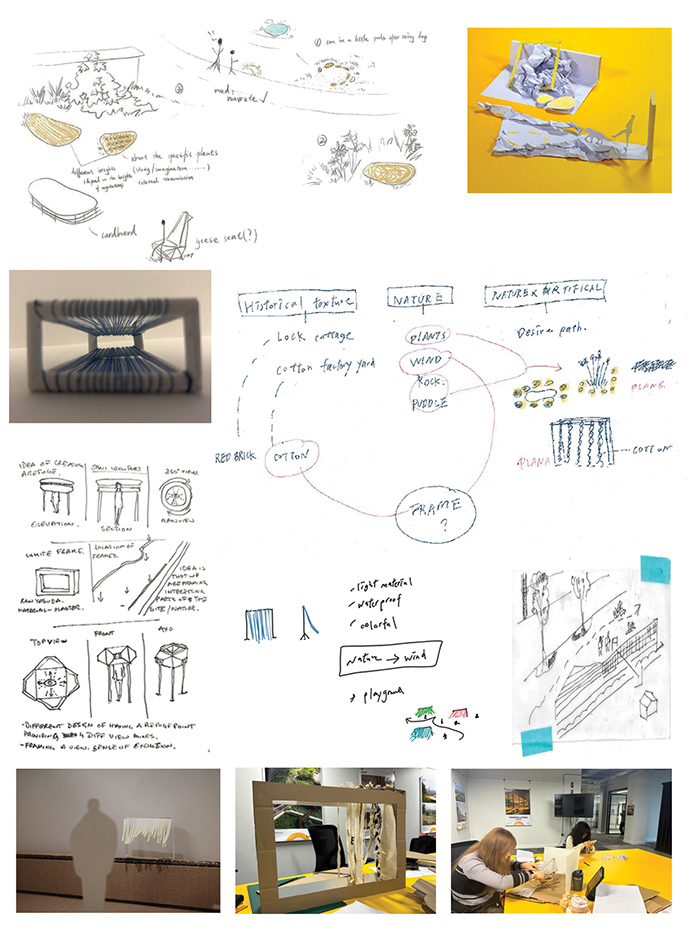

Building on a shared understanding of the site’s emotive qualities and fluctuating characteristics, students collaborate in groups to test concepts and prototypes for ephemeral installations. These aim to create moments of human connection with natural phenomena. Students explore ideas individually to support the negotiation of a final group proposal. By foregrounding encounters with nature, the project encourages students to reimagine environmental relationships and explore new possibilities for the landscape to act as an ecological-cultural mediator.

The project culminates in the design and construction of a 1:1, human-scale intervention installed on site. These temporary installations are designed to be easily assembled and accessible, offering both site users and the student cohort opportunities to engage with the work in a sensory and experiential manner. Students observe and document how others interact with their installations, allowing them to reflect on and evaluate these encounters considering their original design intentions. The unpredictability of site conditions and to an extent, human behaviour, often leads to unexpected outcomes, bringing moments of surprise, delight, and, at times, dismay to students.

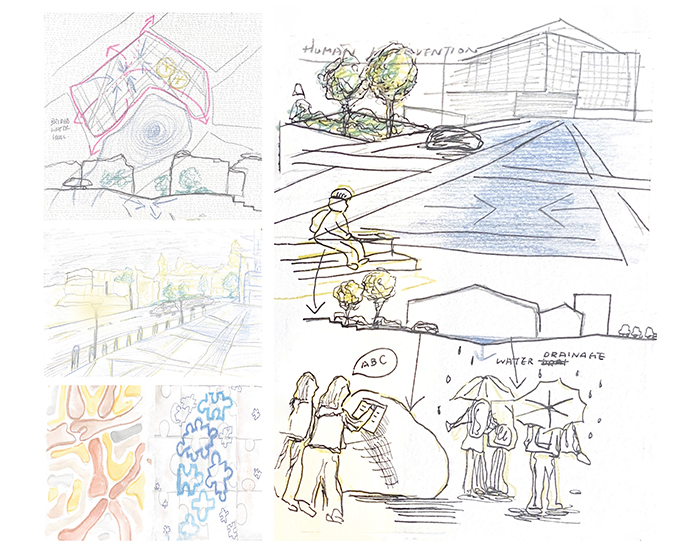

Figure 4. Testing ideas for an ephemeral installation. Student Group names: Yuxin Fang, Amrit Gurung, Ninghung Kao, Hongyu Ren, Xiaoxi Tang.

Peer-to-peer engagement and critique further enrich this phase, revealing diverse perspectives on the experiential and emotional impact of their work. Through this process of design, realisation, and reflection, students actively engage with Schön’s (1991) concepts of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action, embedded within the intensity of this four-week learning period.

Reflections

The project serves as a framework for reading and writing the landscape, while developing techniques for creative expression. The landscape narrative is prioritised, and an emphasis is placed on human-nature interactions. We aim for students to ‘transcend the clinical analysis of layers and structures and to dig for the signs of the living – to learn landscape language and how to read its stories’.

Figure 5. Final installation on site (as developed in figure 4). Image credit: Yuki Iijima | Student Group names: Yuxin Fang, Amrit Gurung, Ninghung Kao, Hongyu Ren, Xiaoxi Tang.

It establishes a platform for sharing multicultural perspectives on natural phenomena in urban contexts. The identification of a common language becomes the interface for a collective exploration of landscape, not only as a conceptual framework, but also as a deeply embodied experience, rich with complexity and meaning.

Students are empowered to take ownership of the design process and decision-making, from ideation and material selection to testing, choosing the installation site, and shaping collaborative practices. The framework provides students with a supportive structure which incentivises them to develop agency in their work and explore creative artistic expression. Experience and exploration are emphasised, over the perceived ‘quality’ of the outcome.

The site is transformed into a stage for enactments. The act of assembling and dismantling the design is as much a part of the performance as the final installation. As students interact with the city, they observe how onlookers pause, interact, and engage with the installation. This creates a temporary choreography of movement in urban space, where people become part of the design process.

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the concepts and outcome of a project which draws on observations of natural phenomena manifested in the space. Students stated, ‘The location of the artwork was intentional, as the dappled sunlight filtered through the tree leaves forming interesting patterns on the ground, at the time of our visit. We wanted to create a combination of natural and crafted elements…’.

Figure 6. Iterative design practices. Student group names: Fanope Oluwatofarati, Manhitha Shetty, Akshita Venugopal, Yifan Wang, Chenwei Yu, Ruoqi Zhang.

Figure 7. From sketch to site: a collaborative installation revealing the interplay of nature and urban space. Student group names: Fanope Oluwatofarati, Manhitha Shetty, Akshita Venugopal, Yifan Wang, Chenwei Yu, Ruoqi Zhang.

The images illustrate how this group developed an initial observation into a final installation, through an explorative and collaborative creative process, moving from early sketch ideas, to test models, to onsite installation and, finally, to the recording of serendipitous interactions with ephemeral site conditions. The installation, created using off-cut fragments of coloured vinyl, seemed to intensify awareness of the interplay of wind, rain and light through its movement, transparency and reflectivity. Creative dialogues between the student group led to unexpected dialogues between the human (cultural) and the natural, generating an embodied awareness of urban space as a staging for the complex interplay between environmental and human processes.

Conclusion

Foregrounding the poetic and impermanent qualities of landscape, Ephemeral Installation fosters a critical and creative engagement with place, rooted in embodied experience. Recognising the cultural, educational, and experiential diversity of the student cohort, the project serves as a platform for cross-cultural dialogue around nature in urban contexts. This exchange not only deepens individual understanding but also strengthens the collective capacity to see landscape as a dynamic mediator between the human and the ecological.

Rather than producing fixed or finalised outcomes, early studies function as catalysts for reflection, reinterpretation, and adaptive thinking, mirroring the very qualities that define a healthy ecosystem: diversity, connectedness, and responsiveness to change. In this sense, the project not only models inclusive and ecologically attuned design practices but also embodies a pedagogical approach that values uncertainty, negotiation, and empathy. By reconnecting students with the human scale and the immediacy of place, Ephemeral Installation reasserts the landscape architect’s role in restoring meaningful relationships within the urban ecosystem, socially, culturally, and ecologically.

____________

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions from tutors and lecturers in the MLA programme at Manchester School of Architecture.

Notes

Vygotsky, L.S., Rieber, R.W. and Carton, A.S. (2016) The Collected Works of L.S. Vygotsky: Volume 1: Problems of General Psychology, Including the Volume Thinking and Speech. New York, NY: Springer.

Coles, R. and Costa, S. (2023) Biophilic Connections and Environmental Encounters in the Urban Age: Frameworks and Interdisciplinary Practice in the Built Environment. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, pp 100.

Schon, D.A. (1991) The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Timmerman, M. (2014).’Reading a landscape’. Topos-The Narrative of Landscape, 88, pp.22.

Note about the authors

Dawn Parke is a Senior Lecturer in Landscape Architecture and Programme Lead for the Master of Landscape Architecture at the MSA. She has extensive multidisciplinary and international experience in both practice and academia, which has shaped her understanding of collaborative and cross-disciplinary approaches across a variety of contexts and scales.

Eddy Fox is a Senior Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at the Manchester School of Architecture, where he has worked for the last 15 years, teaching on Urbanism and Architecture programmes and collaborating with courses in Barcelona and La Coruña. Previously, he spent more than a decade working as a Landscape Architect in various practices around Manchester. Other articles in Crítica Urbana: Reconstructing the rural. The Role of Landscape Architecture in Reimagining the UK’s Rural Landscape and Requiem por Ryebank

Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon is a Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at the Manchester School of Architecture. He has worked on landscape design and masterplanning projects of varying scales around the world and taught in both India and the UK. Sandeep is also on the Editorial Advisory Panel for the Landscape Journal, UK and the Education Board, ISOLA, India.

Para citar este artículo:

Dawn Parke, Eddy Fox and Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon. Encountering Space. Crítica Urbana. Revista de Estudios Urbanos y Territoriales Vol. 8, núm. 37, Arquitectura, ¿para quién? A Coruña: Crítica Urbana, septiembre 2025.